Book #02

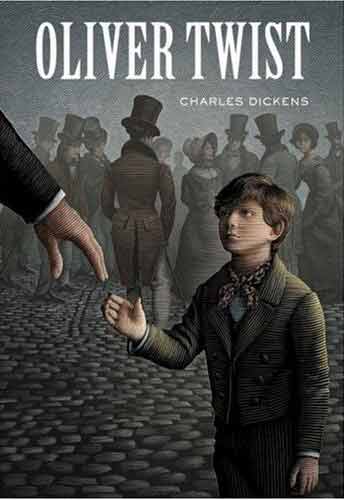

Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens

Oliver Twist is born in the humble backstreets of a nameless town to an extraordinary future. He will travel to London and be initiated into to a gang of petty crooks. He will find himself at the centre of a criminal plot and an infamous murder, the object of hope, fear, despair and unexpected goodness. His story is peopled by thieves and prostitutes, coloured by violence and neglect, and redeemed by the innocence of one boy searching for a home.

I'm starting to really believe classics are my comfort blanket. I could read as much contemporary literature as I could stomach, and nothing will beat coming back to Dickens, Austen, or Hardy. I feel so twee announcing them as my favourites, but it is so irrevocably true. Truly nothing can beat them, and I am now one of those people who blindly can't understand those who don't enjoy a classic. Make note of this.

What we have here is an utterly blistering commentary from Dickens on Victorian Poor Laws in the first half of the 19th century. His bitter sarcasm endears us to Oliver's situation, and Dickens uses him to showcase the wrongdoings of those who use the desperation of the poor for their own gain. We see orphanages where children are worked to the bone to turn a profit, and workhouses where the perception is that poverty is the result of the people being idle. There are jokes made about giving inmates as little food as possible, which will mean only smaller coffins would be needed. Although Dickens writes with sarcasm and humour, it's very black, and very bitter.

The writing, as always with Dickens, is lyrical, and your eyes glide over his illustrious depictions of crime-ridden Victorian London. In contrast to this, however, are Dickens' sharp comments on socialism which bring you to your senses suddenly. This becomes particularly apparent as Oliver escapes the workhouse, and runs to London. It's clear that this is Dickens' city, and he describes the streets, location and aesthetics, as though he were showing us a map or a photograph. The prose becomes more gooey and smooth, as though Dickens was now able to relax in a different setting, away from the workhouse.

I loved the whole band of merry villains; the cheeky Artful Dodger with his quick fingers and even quicker tongue, the maturity decider Master Bates, the totally flawed but golden-hearted Nancy, the truly awful Sykes, and even the nippy wee dog. Most of all, I loved that most of the characters were given names descriptive of their characters. Mrs Mann, the shockingly un-maternal orphanage owner, who put her children to work rather than mothering them; Toby Crackit, the housebreaker; Mr Grimwig, who seems mean initially, but changes into a kindly gentleman as though removing a mask (or wig!); and Blathers and Duff, entirely useless police detectives. There were more, but these were my favourites, and it's difficult to dispute the cleverness of the names.

Despite each of the characters having a strong hold on me, Fagin was, by far, my favourite. I'm aware he's the product of Dickens' anti-Semitism, with Fagin being represented as parody of all Jews, with all of his negative traits seeming to be inherently linked to his religion. This was always at the front of my mind when reading the novel, however Fagin is one of the most wonderful villains I've ever encountered. He is dark, rich, and perfectly evil; described as incredibly grotesque to look at, he shows no remorse for children who have been sent to jail, or put to death, for working with him. When we meet Nancy we understand the consequences of meeting Fagin as a young child, and see what a life of working under his instruction has made of her. Ironically, Fagin is the catalyst for Nancy's exit in the novel. I truly feel Fagin here is the devil personified, with Dickens referring to him as 'the merry old gentleman' which seems to suggest such a symbol.

Dickens completely and utterly makes use of deux et machina to create a happy ending for our 'good' characters. I may be in the minority when I find this totally excusable; why shouldn't they all live happily ever after? In a novel of such squalor, depression, devastation and cruelty, it feels good to come through it all and see a happy group of characters.

This is absolutely one of those novels everyone should read, although not everyone will. It's a social commentary, a moral lesson, and an instruction on the social inequalities of poverty. The characters are gorgeous, the prose is wonderful, and the lesson just. An incredible classic.