Book #26

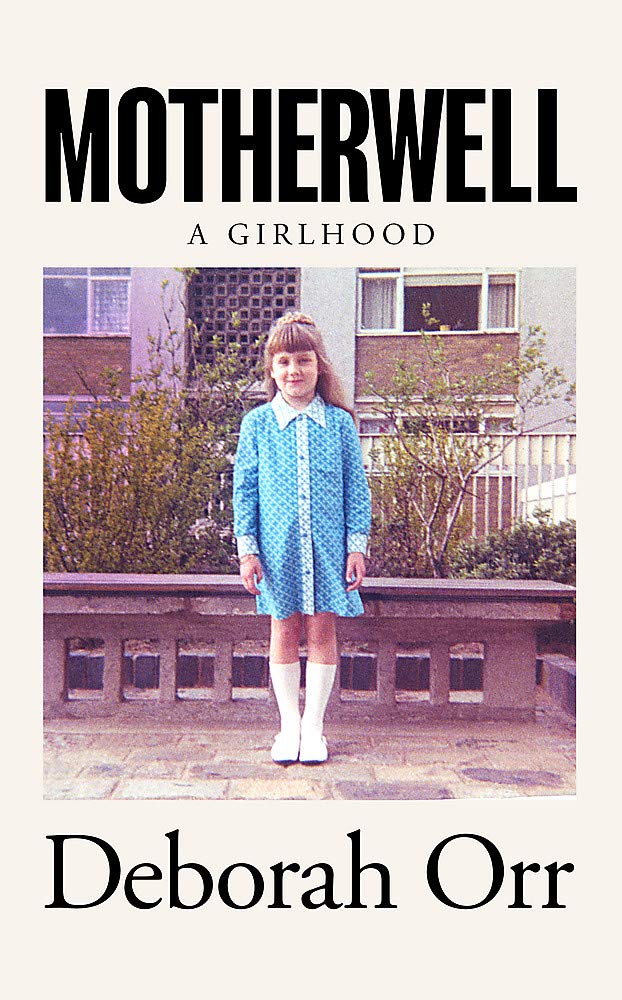

Motherwell: a Girlhood by Deborah Orr

Just shy of 18, Deborah Orr left Motherwell - the town she both loved and hated - to go to university. It was a decision her mother railed against from the moment the idea was raised. Win had very little agency in the world, every choice was determined by the men in her life. And strangely, she wanted the same for her daughter. Attending university wasn't for the likes of the Orr family. Worse still, it would mean leaving Win behind - and Win wanted Deborah with her at all times, rather like she wanted her arm with her at all times. But while she managed to escape, Deborah's severing from her family was only superficial. She continued to travel back to Motherwell, fantasizing about the day that Win might come to accept her as good enough. Though of course it was never meant to be.

This is, quite possibly, the most wonderful memoir I’ve ever read.

Growing up in Motherwell in the sixties and seventies, Orr experienced a range of situations and emotions prevalent in working class towns in Lanarkshire. She speaks of class, of industrialisation, of politics, and, most importantly, of family life. Most of all, she speaks of her fractious relationship with her mother, at a time when expectations for women were simple, limited, and soon to be outdated.

Although I grew up in Lanarkshire myself, and was delighted to identify places I knew within the pages, my coming of age was some thirty years after Orr. I was enthralled by the history of Motherwell, and deeply interested in some of the things which have not, and probably will not, ever change. Orr was close to my own mother’s age, so it was wonderful to read and imagine her growing up in a similar environment.

As she recalls emptying her mother’s home after her death, she describes objects she finds and the memories they evoke. This is spine-tingling; an almost-eulogy to a life lived long ago, the only remnants of which remain in a house which once held Orr’s whole world. It feels so deeply personal that it’s almost voyeuristic to experience these remembrances, these tokens held on to for decades.

Somehow the words are painful and uplifting all at once. Orr’s childhood, the experiences which shaped her, the people who created flaws in her, and those who did the opposite, haunt the pages like ghostly emblems of change.

Whilst painting a picture of her youth, Orr makes sure to tell us that she now understands most of the psychology behind her own behaviours, and those of her family. She speaks of narcissism quite heavily, of how trauma can affect us, what causes us to treat people in the ways we do. She doesn’t blame, she simply comments on her observations. It seems this enlightenment brought her understanding, if not peace.

There is no retribution here, no defining moment of success. Orr’s eventual desertion of Motherwell never did heal any wounds, nor mend any relationships. Despite her glowing career, she never did achieve what she wanted most of all, and that’s what set my eyes to water.