Book #10

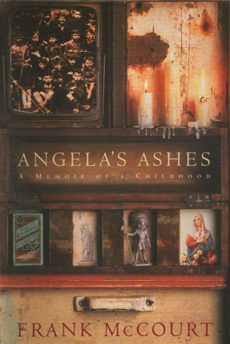

Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt

The Pulitzer Prize winning memoir of Frank McCourt, born in Depression-era Brooklyn to recent Irish immigrants and raised in the slums of Limerick, Ireland. Frank's mother, Angela, has no money to feed the children since Frank's father, Malachy, rarely works, and when he does he drinks his wages. Yet Malachy-- exasperating, irresponsible and beguiling-- does nurture in Frank an appetite for the one thing he can provide: a story. Frank lives for his father's tales of Cuchulain, who saved Ireland, and of the Angel on the Seventh Step, who brings his mother babies.

This must be the collection of memoirs I hold the most love for. As a blessed girl of ten years, I remember first reading this novel of poverty, hunger, dirt, and mortality, beside a pool somewhere in the sun. I had finished whichever book I had been bought in the airport’s WH Smith, and had decided to move on to my mum’s novel of choice. I was captivated, and it stuck with me.

Of course, being ten, a lot of the themes and issues would have washed over me entirely. Twenty years later, they have broken me. Born to Irish parents in New York, Frank was ripped away from the city of dreams after his father’s alcoholism plunged the family into poverty. Upon their return to Ireland, the McCourts stumble through life, living hand to mouth, with Frank’s father continuing to drink either his wages or the dole money. They suffer hunger and shame, they lose each other, bury each other, and become more and more despondent after every setback.

Written from the point of view of his younger self, McCourt shows us his family’s struggles from innocent eyes. We see him try to understand some of the things happening to them, and see him react childishly and recklessly. An alcoholic father and a despairing mother do not make for the best upbringing, so Frank learns his own lessons about life and morals mainly through making mistakes, then going to the priest to confess.

Hearing this story from the mouth of a young boy makes the themes all the more painful, yet impossibly endearing. Where McCourt will fill one page with grim hopelessness, the next will give us witticisms only found in Ireland, young men having the time of their lives in clothes “hanging off their arses”, and a community banding together in kindness.

McCourt’s writing is so tangible and engaging that it’s difficult to believe it’s not fiction, but it’s very important to remember the truth of all this. The most heartbreaking thing is realising this all happened to one boy, in one family, but also to many many others.

A dark story of deprivation and delight in equal measures, McCourt has depicted his Depression-era childhood beautifully, and I only wish my words here could do him the tiniest justice. It’s a wonder. ‘Tis.